Bulletin of Remarkable Trees Vol. 3 No. 3

How the University of Illinois and Morton Arboretum are connected by a long horticultural thread

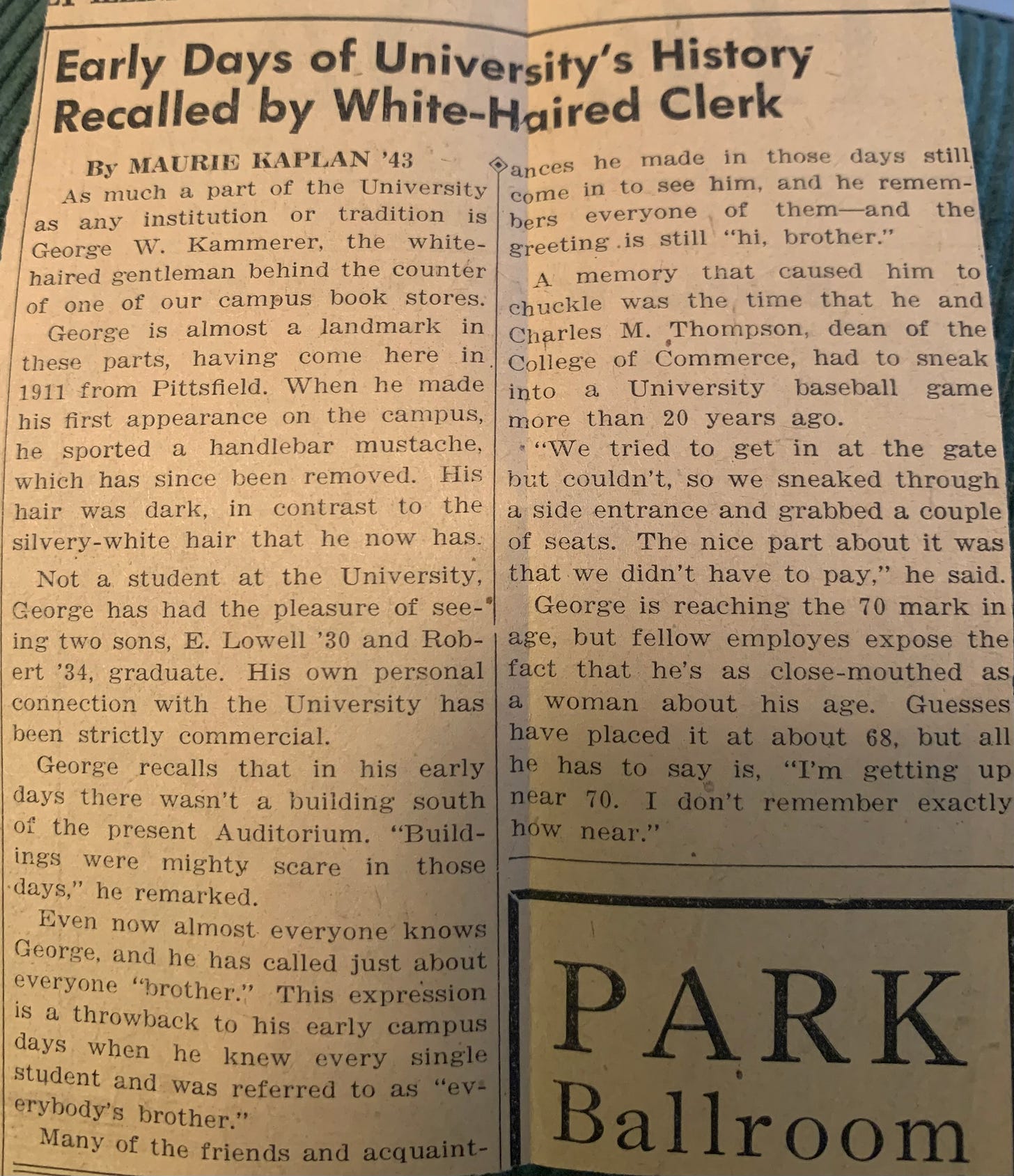

A theme that has come up continuously in my time researching and writing this newsletter is that many of the institutions we residents of Chicagoland treasure are connected—often in ways that aren’t readily apparent. My grandpa, and his work as Curator of Collections and landscape architect at the Morton Arboretum, has a direct connection to the University of Illinois system—he graduated from the U of I main campus in Champaign-Urbana with a degree in landscape architecture in 1928. The University was one of the first to offer a degree program in landscape architecture, beginning in 1907. The program continued on its progressive arc and, in the late 1910s, hired two women as teaching associates. One of whom, Betty McAdams, went on to become a well-known landscape designer in the Chicago area and was a teacher and mentor to my grandfather. The Kammerer family had roots in Champaign even before my grandfather attended school at U of I—his father worked at the University’s co-op bookstore for decades.

Beyond Champaign, the U of I campus, and the landscape architecture program, the love and keen interest my grandfather cultivated for plants and nature followed him from his family’s home and his alma mater to the gardens, forests, and prairie of the Morton Arboretum.

If you’ve ever driven down Finley Road in Downers Grove, bordering the Southeast side of the Morton Arboretum and following the curved path of I-355, you might have noticed an unassuming sign for the UIC College of Pharmacy Pharmacognosy Field Station (previously the University of Illinois Drug and Horticultural Experiment Station, with the name changed later on in its life to help prevent break-ins and curious trespassers). While only tangentially affiliated with the Morton Arboretum, their histories intertwine.

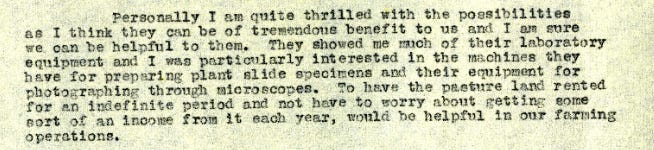

In a 1944 letter, Clarence Godshalk describes to Jean Morton Cudahy a meeting with Dr. Wirth and Dean Serles of the UIC College of Pharmacy. The pair outlined a proposal to rent forty-four acres on the Morton Arboretum’s east edge to develop and maintain a nursery of plants with the goal of experimental drug research.

The University began leasing said land on the Arboretum’s east side for their Drug and Horticultural Experiment Station in 1945. The outpost continued to be expanded upon throughout the following years, adding a state-of-the-art (for its time) greenhouse facility in 1965:

Beyond land, the Morton Arboretum to UIC connection extended to employees. Floyd Swink was an example of this: he was a professor of Botany at UIC’s College of Pharmacy and later, in 1960, a Naturalist and Taxonomist at the Arboretum, focusing specifically on educational programs.

The connectivity between Illinois’ University system, my grandfather, and the Arboretum was particularly evident to me this past April (and again in May). While walking through the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) Medical Campus in the city’s Medical District, I took a stroll through the Dorothy Bradley Atkins Medicinal Plant Garden.

Smack in the middle of a distinctly modern campus notable for its brutal architecture is hardly the place one expects to find a sunken garden. But this educational (and beautiful) spot extends upon the mission UIC undertook at the Arboretum—investigating and sharing uses for plants many of us take for granted in our yards and public spaces.

Over 150 species with known or potential medicinal uses are represented in the garden, reflecting both the College’s research foci and a general overview of plant medicine. While not directly linked to each other (best I can tell), this unique garden and the Morton Arboretum share a common set of goals—research, education, and providing beautiful spaces to foster plant knowledge and appreciation.

While some of these connections can feel serendipitous, in reality, they reflect a focus on interconnectedness that so many Chicagoland institutions actively prioritized and valued. The Arboretum grew and maintained relationships with other gardens, museums, and organizations in the Chicago area and worldwide. And in doing so extended the reach of their impact far beyond the property’s now 1,700 acres. We are fortunate that so many past horticulturists, researchers, landscape designers, and plant lovers (like Grandpa Kammerer) worked tirelessly to ensure that future generations could access the space, knowledge, and connection they valued so deeply.

If you have topics you’re interested to hear more about or feedback for me, please feel free to let me know in the comments.

If you like what you’ve read so far, sharing Bulletin of Remarkable Trees with your friends would help a whole lot!